University Archives and Special Collections is conscious of its responsibility to collect IIT’s history back to its earliest roots, including its relations with its neighborhood. In the fall of 2018, the unit discovered a scrapbook on eBay that had been assembled by an Armour Institute student in around 1910. The posting’s sample photographs demonstrated that the scrapbook not only documented aspects of on-campus student life, but also people and institutions of the surrounding neighborhood. On the strength of that evaluation, UASC and Galvin Library decided to purchase the scrapbook.

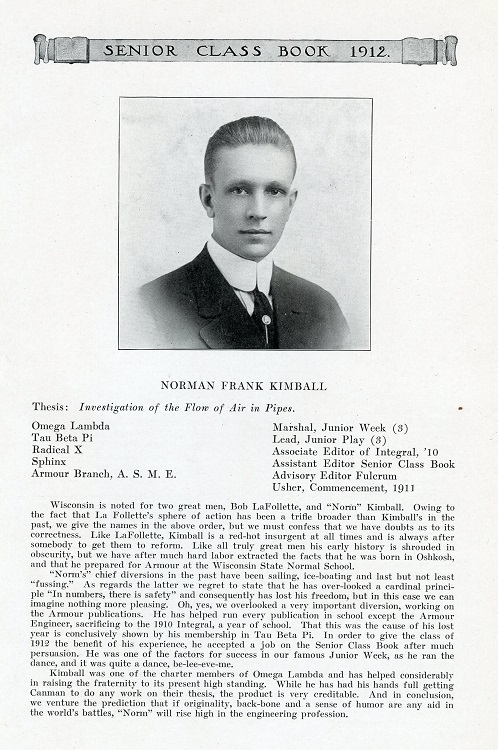

The scrapbook is strong in internal evidence, and it did not take long to identify its creator as Norman Frank Kimball (1890-1972), a 1912 graduate of Armour Institute’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. His senior portrait and biography attest to his role as one of the school’s most socially active students. In the parlance of the time, he was a “fusser”--a supreme social mixer—which enabled him to organize campus dances, edit publications, power fraternities, organize off-campus sporting excursions, and assemble a first-rate document of his life and times at Armour.

Such personal scrapbooks usually remain in family hands for generations. Though Kimball did marry and relocate to New Hartford, New York, we have as yet uncovered no evidence that he had children. At any rate, the scrapbook found its way to the market and we at Illinois Tech are fortunate that it did.

The scrapbook tells dozens of tales: photos of young ladies, fellow male students (Armour’s student body was all-male at the time), athletic events, and off-campus excursions; dance cards; advertisements from local dance halls and theaters; programs from campus theatrical and musical performances. One cannot do justice to the scrapbook in a single essay, and I intend to highlight and discuss various aspects of its contents in additional essays.

During this week, which began with the observance of the 90th anniversary of the birth of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., it is right and fitting to consider the scrapbook’s documentation of Armour’s relationship with its neighborhood. Many textbooks on Chicago history discuss how Chicago’s South Side “Black Belt” (an area of contiguous African-American settlement, anchored largely on State Street of only a few blocks width but many blocks long north to south) was largely the product of the Great Migration of Southern Blacks to Chicago in the period 1910-1930. This is true only to an extent. In reality, African Americans had been involved in Chicago’s development from the very beginning, and many were already on the South Side in appreciable numbers long before 1910. U.S. census schedules demonstrate that when Armour Institute was founded on 33rd and Federal in 1892, the neighborhood immediately to the north of 33rd Street was already a majority Black neighborhood. This is significant. It means that the founders of Armour Institute (Philip Danforth Armour, donor; and Frank Wakeley Gunsaulus, its first president) had a commitment to educational mission in an ethnically and racially diverse neighborhood from the outset. In that long period from the end of Reconstruction in the U.S. (1877) until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, national civic and educational institutions had the option of following either integrationist or segregationist models. P.D. Armour and Frank Gunsaulus clearly founded the new school on the integrationist model, and early yearbooks from Armour bear this out. Many on campus and beyond are aware that Charles Warner Pierce graduated from Armour in 1901 as the nation's first-known African-American degree-holding chemical engineer.

With the death of P.D. Armour in 1901, however, his school’s commitment to racial and gender inclusivity quickly faded—and all circumstantial evidence points to the attitudes of his son, who took over as the school’s primary patron. By 1902 all racial minorities and co-eds were gone from campus, not to return until Armour merged with Lewis Institute (which had retained the integrationist model) in 1940 and adopted Armour’s campus for the new Illinois Institute of Technology.

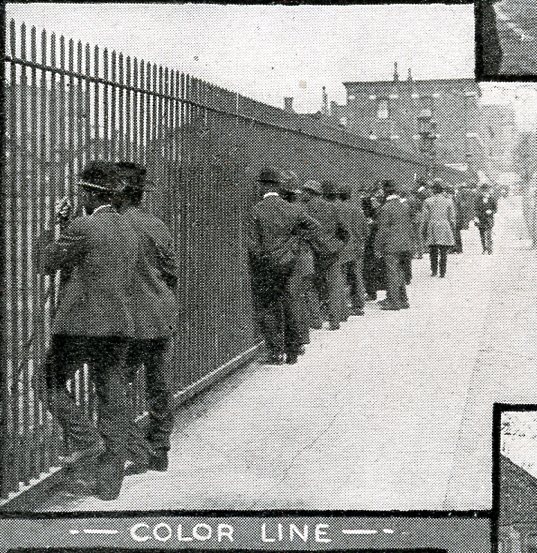

The Armour yearbooks after 1900 provide evidence of this change. No longer admitted as students, local African-Americans were now only documented on campus as observers. On page 187 of the 1909 Integral (the Armour Tech yearbook), one sees a small photo of African Americans on the north side of 33rd Street, standing at an iron fence and observing an Armour athletic event with in the fence; it is captioned “Color Line.” Just a few years before, the very spot of that athletic field had housed a Black neighborhood—but had been cleared by the Armour family in 1904 for the field. The line was of recent vintage, indeed.

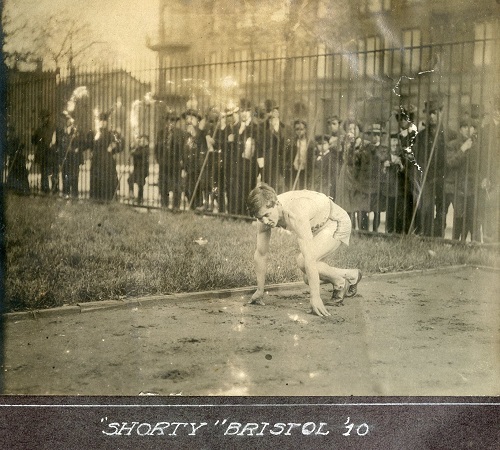

Shorty Bristol, Norman Frank Kimball scrapbook

On this topic, Kimball’s scrapbook does not disappoint. While the 1909 yearbook shows the observers on the outside, photographed obliquely (with no faces shown), a photo in the scrapbook shows the observers as seen from the inside—faces and all. Admittedly they were only backdrop to his friend “Shorty” Bristol, who is about to run a race. But this photo is an excellent snapshot of the neighborhood composition nonetheless.

Not intended for publication, Kimball’s scrapbook is refreshingly free of the degrading social commentary and stereotypes which often accompanied pre-1964 portrayals. For this neutral documentation from ca. 1910 we thank Kimball—and for our ongoing liberation from stereotypes after 1964, we thank Dr. King.

Mindy Pugh, University Archivist, 1/22/2019

Image Credits

Norman Frank Kimball: 1912 Armour Institute of Technology Senior Class Book

The Color Line: 1909 Integral

Shorty Bristol: Norman Frank Kimball scrapbook